Where the Music Takes Flight: The Nuances of Musical Theatre

Below is a polished English translation that preserves the essay-like tone, key concepts (especially 「craft」), and the performers’ lived, practice-based perspective. It is suitable for program notes, documentation, or publication.

“Photography is allowed today, but video recording is not.”

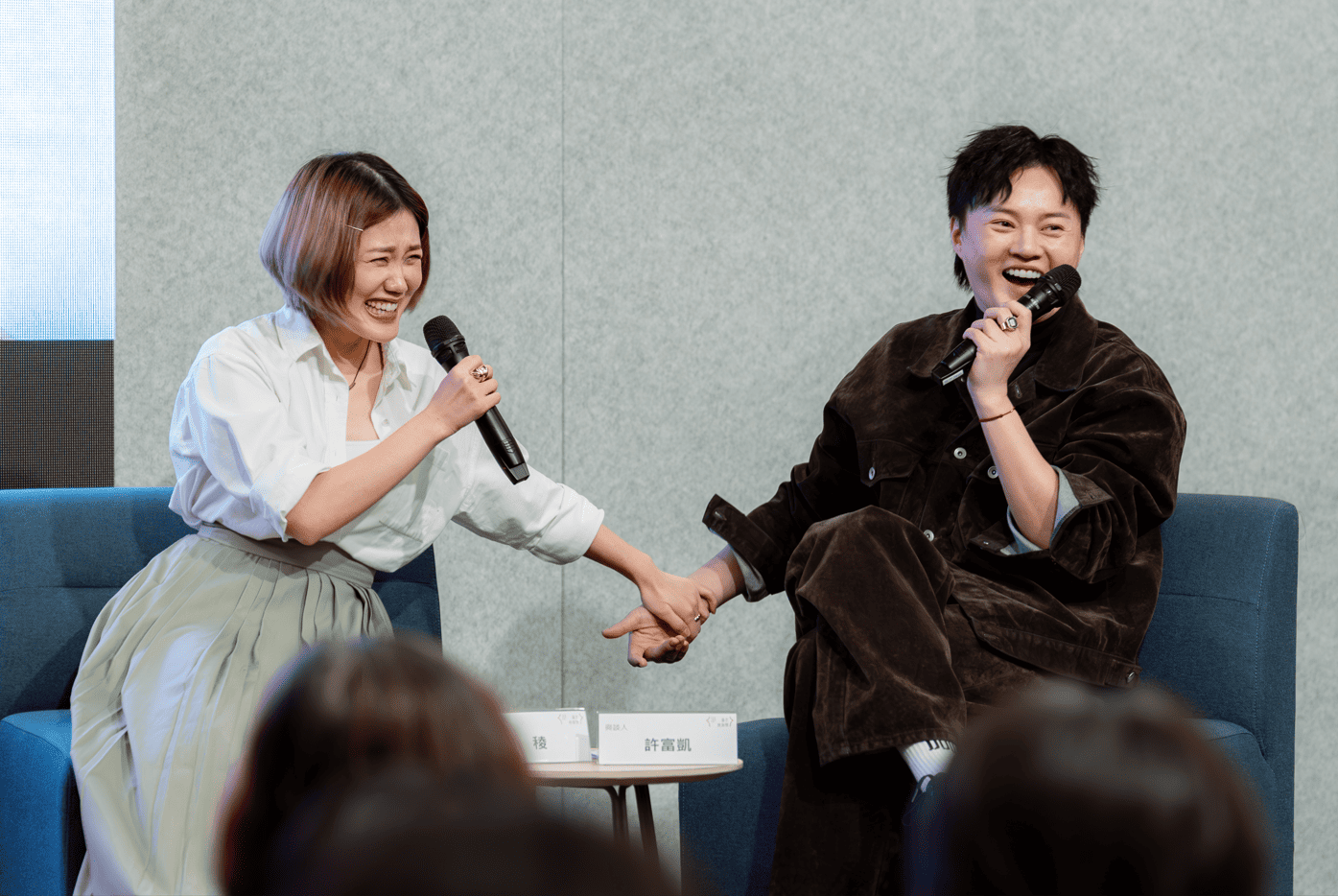

The lecture began with this reminder. The sentence was brief, yet it inadvertently defined the nature of the event: an exchange generated in the moment, rather than a record that could be fully reproduced. Host Chang Ya-hsuan introduced the speakers—Hsu Fu-kai, winner of the Best Actor in a Musical award at the inaugural Taipei Theatre Awards, and Chang Leng, winner of Best Actress in a Musical. Both were first-time award recipients, yet they came from markedly different performance systems. That juxtaposition became a condition stated from the very beginning.

The lecture’s title, “The Tricks of the Trade in Musical Theatre”, did not point to a single technique or a neat success story. Instead, it attempted to return to those recurring moments in performance work that are difficult to clearly name—moments of judgment. The term “craft” refers to decisive details embedded in experience: a felt sense of choice that takes shape through long-term practice and correction, and is often recognizable only through retrospection and dialogue.

Hsu Fu-kai and Chang Leng shared the same awards category, but their backgrounds and training trajectories hardly overlapped. One has long centered singing, with an intimate understanding of how voice carries emotion and narrative; the other comes through theatre training, accustomed to building the stage through body, rhythm, and relationships between characters. Chang Ya-hsuan noted that the development of musical theatre in Taiwan has not followed a linear path, and only in recent years has it become more widely seen by audiences and supported by greater resources. Precisely at such a moment, placing creators of different backgrounds side by side is not about establishing a model, but about returning to a concrete question: when music, drama, and performance are placed on the same stage, what kinds of choices do practitioners face—choices that cannot be simplified?

Still half-confused about what I was doing, I was already pushed onto the stage

Before speaking about musical theatre, Chang Leng chose to return to the act of standing on stage itself. She did not begin with musical theatre as a genre, but went back to childhood—a period before one can truly choose what one becomes.

“I’m not formally trained,” she said, adding that her earliest and deepest connection to performance actually came from Peking opera. Her parents met through Peking opera, and when she was still very young—before she had any clear awareness of what performance was—her mother brought her to learn.

“When I was still half-confused and didn’t know what I was doing, I was pushed onto the stage.”

Learning Peking opera, for her, was less a personal aspiration than an arrangement embedded in family structure. Yet the long-term training left deep traces in her body. The demands of vocal line, resonance, rhythm, and movement made her accustomed from early on to coordinating voice and body. These abilities surfaced naturally in school life, and later became an important foundation for her entering the Department of Theatre Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts. She emphasized that at the time, the department’s training focus was still largely oriented toward spoken drama; musical theatre was not a primary direction.

“Singing” is a professional technique that must be managed, not simply an impulse to perform

Her first direct contact with musical theatre came during her university graduation production. She recalled that the school produced The Marriage of Figaro, adapted from opera into a musical-theatre form—also her “first time ever performing in a musical.” She did not frame this as a smooth transition. Instead, she admitted plainly: “Back then, I actually didn’t know how to sing.”

Even with vocal conditions and stage experience, her understanding of musical theatre singing was limited. Without systematic training, she used incorrect vocal production in performance, placing excessive pressure on her vocal folds. After multiple consecutive high-intensity shows, she developed vocal issues—“soft nodules on my vocal folds,” as she put it.

This was the moment she truly realized that musical theatre singing is not supported simply by “being able to sing” or “being able to act.” It must simultaneously carry character state, physical rhythm, and emotional progression. And with repeated performances, physical depletion, and the instability of the body, singing stops being a simple act.

“You’re not just singing,” she said. “You have to deal with so many contingencies—including your own body.”

To protect her voice during that period, she almost stopped speaking altogether, which led classmates to misread her as distant or unapproachable.

“They didn’t know that inside, I was panicking.”

Alongside physical discomfort, the psychological pressure was equally heavy; she recalled needing sleeping pills to get through the nights. This experience became a critical point she could never bypass when approaching musical theatre thereafter—not a “setback” to be simplified, but a turning point that forced her to re-understand the relationship between voice and body.

For Chang Leng, musical-theatre singing is highly technical labor: voice must carry character state, physical rhythm, and emotional propulsion; it cannot exist independently. From that point on, she began to treat singing as a professional technique that must be actively managed, rather than a pure performative impulse.

In truth, we are all extensions of our parents’ dreams

Unlike Chang Leng, who traced her performance roots to childhood opera training, Hsu Fu-kai did not begin by talking about performance as such, but about listening. He described himself as having “been listening to songs since I was in my mother’s womb.” These auditory memories did not come from classrooms or stages, but from everyday life.

His family ran a hairdressing business. When his mother worked in the salon, she would place him—still very young—in a cradle nearby; his father repeatedly played videotapes of Chu Ke-liang’s restaurant-show performances. This became Hsu’s earliest musical environment.

“People often ask why I know so many old songs,” he said. “It’s actually because I heard them from those tapes.”

His first time standing on stage was at a wedding in third grade, when he was suddenly coaxed into singing.

“That was my first time on stage.”

After he sang, someone told his father: “Your kid can sing. Why don’t you let him learn properly?” That remark became the starting point of formal vocal training.

Looking back, Hsu was clear that it was not his own will that drove the path, but his father’s arrangement. Competitions, practice routines, teachers—these structures were put in place before he was fully capable of choosing.

“In truth,” he said, “we are all extensions of our parents’ dreams.”

Only when I could understand and choose did singing become bearable—and even enjoyable again

One key difference, Hsu noted, was that he became aware early on that the voice is a tool that must be protected. He spoke specifically about puberty and the voice change. When his voice began shifting, his parents decided that he should stop singing entirely. From junior high through senior high, he barely practiced at all, waiting for his voice to stabilize.

“Every day, I just tested where my voice had changed to.”

For someone accustomed to singing, this was not easy. Yet in hindsight, he saw it as an important decision. After the voice change, he had to relearn how to use his voice from the ground up: resonance placement changed; range and strength required recalibration. This “starting over” cultivated a work habit of high bodily awareness.

He also admitted that when singing became “a job that must be executed every day,” joy was no longer guaranteed.

“When I was young, I actually wasn’t happy.”

Being required to practice for hours each day felt like a burden. Only after he became an adult—able to understand the rhythm of work and choose how to collaborate—did singing become bearable again, and even something he could enjoy. Voice is not a natural outpouring of inspiration; it is a tool that requires long-term maintenance, adjustment, and restraint. That attitude, he suggested, later enabled him to translate his experience as a singer into a performance form with even greater physical demands and more complex rhythmic structure.

Musical theatre is an entirely unfamiliar performance system

Compared with Chang Leng’s gradual entry through existing training pathways, Hsu Fu-kai’s entry was notably contingent. He recalled that when he first received a musical-theatre invitation, his instinct was immediate refusal.

“My first reaction was: no.”

The reason was straightforward: he had no acting experience, and he did not believe he was ready to enter a completely unfamiliar performance system.

What changed his mind was not a sudden understanding of musical theatre, but the gentle push of a close work partner, who simply suggested he “go talk to the troupe first”—without promising an outcome or presuming a role. In that half-reluctant state, Hsu walked into his first musical-theatre rehearsal room.

He described himself at the beginning as “understanding nothing”: unfamiliar with rehearsal processes, unfamiliar with musical-theatre actors, with only one certainty—he could sing well. That single strength allowed him to stand his ground temporarily. The rehearsal team understood his background and deliberately offered flexibility: “You perform first, and we’ll adjust from there.” This allowed him to begin from voice and gradually learn how drama functions.

But this did not mean the process was pressure-free. He emphasized that musical theatre often performs without microphones, requiring the voice to project across the space directly. Under such conditions, voice and body cannot be treated separately; every movement, placement, and psychological state affects vocal stability. For him, the first musical was not a “successful crossover,” but a process of recalibrating his existing professionalism.

How to understand “acting” in musical theatre: Hsu Fu-kai on Wutai University

When discussing his award-winning work Wutai University: Queen of the Night, Sakurako Mama (adapted from his album Wutai University), Hsu did not begin with the completeness of character. Instead, he returned to a more fundamental question: how did he come to understand what “acting” means in musical theatre?

Before entering Wutai University, his imagination of acting remained at the level of “performing emotion.”

“I was actually scared,” he admitted. “Because I didn’t know how to act.”

This was not modesty, but a plain description of reality: voice and singing could be handled through existing experience, but character relations and dramatic structure were entirely unfamiliar terrain.

In early rehearsals, he often felt he “couldn’t find what the point was.” When directors and actors discussed motivation, situation, and the rhythm of action, he needed more time to absorb and translate.

“Sometimes I honestly didn’t really understand what they were talking about.”

In musical theatre, singing is not a separate vocal display; it is part of a character’s action.

“If the character is exhausted but you sing too beautifully, the audience actually gets pulled out of it.”

He therefore began to adjust his use of voice so that technique would submit to character state—intentionally preserving roughness in some sections, even allowing the voice to be “incomplete.”

“You have to take away a little bit of what you’re best at.”

Looking back, he did not treat the award as an endpoint, but as a moment in which he first truly grasped how musical theatre work operates.

Emotions in musical theatre are not released all at once—they are precisely rationed

If Hsu learned “subtraction” in Wutai University, Chang Leng’s experience in Dear Mr. Peter was a long-term state of endurance—one that could not be allowed to become over-consumption. She stated frankly that the production left performers almost no breathing space: dense pacing, an extended emotional line sustained at high tension, and continuous load on both body and mind.

Throughout the lecture, she repeatedly emphasized the importance of restraint. In her view, emotions in musical theatre are not a one-time release, but an energy flow that must be precisely distributed.

“If you use too much in the beginning, there will definitely be problems later.”

This judgment came from observing bodily feedback across repeated performances. Singing, speaking, and movement all involve expenditure; if one overpursues “complete” emotional expression, overall quality may deteriorate—or injury may occur. She rethought the relationship between “emotional truth” and “performance stability”: the goal is not identical intensity every night, but a state that can hold and be repeated.

Looking back on Dear Mr. Peter, she described it as a process that made her “understand my physical limits more deeply.” Musical theatre became not merely a display of voice or character, but a work site requiring sustained concentration and self-regulation—where the performer’s task is not only to carry a character’s emotions, but to keep body and voice continually usable across performance after performance.

Error and letting go

When Chang Ya-hsuan brought the conversation back to the title—the “craft” of musical theatre—neither speaker offered a ready-made answer. Instead, both began from concrete work experience and described those moments in which one must make decisions on the spot—moments that cannot be fully rehearsed in advance.

Hsu spoke first about mistakes. He noted that mistakes are not rare in musical theatre; the real difficulty is how, after a mistake happens, the performance can still remain valid.

“You can’t make every show exactly the same.”

When a section does not go as expected, performers cannot stop and repair it; they can only recalibrate at the next point. This recalibration is not merely technical correction, but judgment about the overall rhythm.

“You have to know how much strength you have left, and how far you still have to go.”

For him, “craft” is not about making every detail perfect, but about knowing when one must preserve something.

Chang responded from another angle: in a long-run performance structure, performers must clearly recognize which parts can be yielded, and which cannot.

“It’s not that every show has to be given at one hundred percent.”

If every performance is treated as an emotional maximum, the body quickly becomes unsustainable. This judgment cannot be fully learned through rehearsal; it comes from cumulative understanding of one’s state after show after show.

Making effective, present-moment judgments within a highly repetitive structure

Across their dialogue, “craft” gradually emerged as an ability positioned between technique and experience. It is neither theory nor mere intuition, but a relationship of trust built over time—between the performer, the body, and the live situation.

Looking back across the lecture, they repeatedly returned to a more basic question: how does one continue making effective judgments in the moment within a highly repetitive performance structure? Musical theatre is not simply the sum of separate professional skills, but a form of work requiring long-term coordination among body, voice, and the conditions of liveness. In such a field, technique is not the endpoint; it is only the prerequisite that allows judgment to hold.

This experience cannot be duplicated, but it can be understood. And for that very reason, “performance” can only truly be heard on site.