Ghost Stories Are the Ultimate Manifestation of “Living:” Ghostopia

Text | Bai Fei-Lan

In comparison to Western pop culture concepts of monsters, such as vampires, zombies, and evil spirits, ghosts in Eastern cultures seem to have more of “a human touch.” After leaving the physical body, “ghosts,” like souls, serve as extensions of human will, emotions, and memories. If given the opportunity to “possess” someone, it is not with an intention to harm. Rather, the purpose is to address those wishes left unfulfilled while alive. From this perspective, “ghosts” are the ultimate manifestation of “life force.”

Ghostopia, produced by approaching theatre, is this kind of ghost story that leaves a lasting impression. Before an exorcist can subdue a female ghost, he is captivated by her tale of two ghosts fighting over a corpse. In that tale, a scholar spending the night in a dilapidated temple is visited by a ghost carrying a corpse, who is followed by another ghost. The two ghosts begin arguing: “I carried it!” “I discovered this corpse!” Dissatisfied with the scholar’s mediation, they dismember the scholar, replacing his limbs and skull with those of the corpse. After the ghosts leave, the scholar is left to ponder who is “I” in this now jumbled body.

The tale of two ghosts fighting over a corpse poses a profound ontological question: What defines us, our body or our soul? Based on this premise, the female ghost guides the exorcist and the audience on a journey back in time to 1950s Malaya. Here, the corpse and scholar, with body parts jumbled and interchanged, become a metaphor for colonial history. Ethnic Chinese people whose families had immigrated generations ago, British military officers loyal to the colonial empire, Malayan Communist guerrillas, and post-World War II political and ethnic turmoil existed on this land. Of course, this somber era was punctuated by intrigue and betrayal, as well as stories of romances that transcended life and death. These all point to a series of core questions: Who am I? Me is who? Who do I want to become and how do I become myself?

This is not the first time that approaching theatre has used a bit of absurdity and dark humor to address the complex history of Malaysia. In 2011, Malaysian theater creator Koh Choon Eiow wrote, directed, and performed in Chronology on Death1. This work was inspired by an event that was reported in the news: a dispute between the government authority in charge of religious affairs and family members over the right to ownership of the remains of a Malaysian Muslim Chinese person. This highlighted the identity dilemma in Malaysia where “death can become a problem.” Koh and another actor navigated through dialogues in multiple languages including Mandarin, Malay, Cantonese, Fujianese, and Hindi, following a simple yet fantastical and absurd narrative, to delve into Chinese funeral customs and the complex bureaucracy of government administration of religious affairs in Malaysia. Amid the humor, this work evoked a profound understanding that crossed cultural backgrounds.

The Malay Peninsula has historically been a place of convergence for Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic civilizations. In the 15th century (Ming dynasty), Zheng He’s maritime expeditions to the Indian Ocean led to the fostering of close ties with ethnic Chinese communities along China’s southeastern coast. In the 19th century, after repelling other European powers, Britain gained dominance as a colonial power and established British Malaya. During World War II, the Japanese briefly occupied this area. After the war, the complex ethnic, religious, and political power structures and identity issues became more pronounced on the Malay Peninsula due to anti-colonialist, nationalist, and communist influences. These historical entanglements, too complex to be explained in a just a few words, formed the creative basis for approaching theatre’s Chronology on Death and Ghostopia. The former involves a dispute between a decedent’s family and religious authorities over possession of a corpse, while the latter uses the tale of two ghosts fighting over a corpse to highlight “feelings of alienation” and even “multiple betrayals.”

Just as identity and name cannot truly define us, the corpse and the scholar are indistinguishable from one another and the actors on stage are not limited to a single role. This is perhaps the greatest freedom that ghost stories bring. The actors “possess” different characters (or rather different characters possess the actors). In addition to the exorcist and female ghost, actors switch identities from a Malayan Communist guerrilla to a new village woman to a British officer. Despite the sudden shifts between male and female and the jumps in time and space, the narrative is not chaotic. Instead, through meticulous design, precisely executed misalignment, juxtaposition, and mixing of languages and accents, the audience is led through a morgue, an ancient temple, an abandoned building, and a Malayan new village. Beautiful imaginings, from romantic aspirations (becoming another person) to revolutionary beliefs (building a better society), crumble and become invalid within a trinity of code words, sweet talk, and secrets.

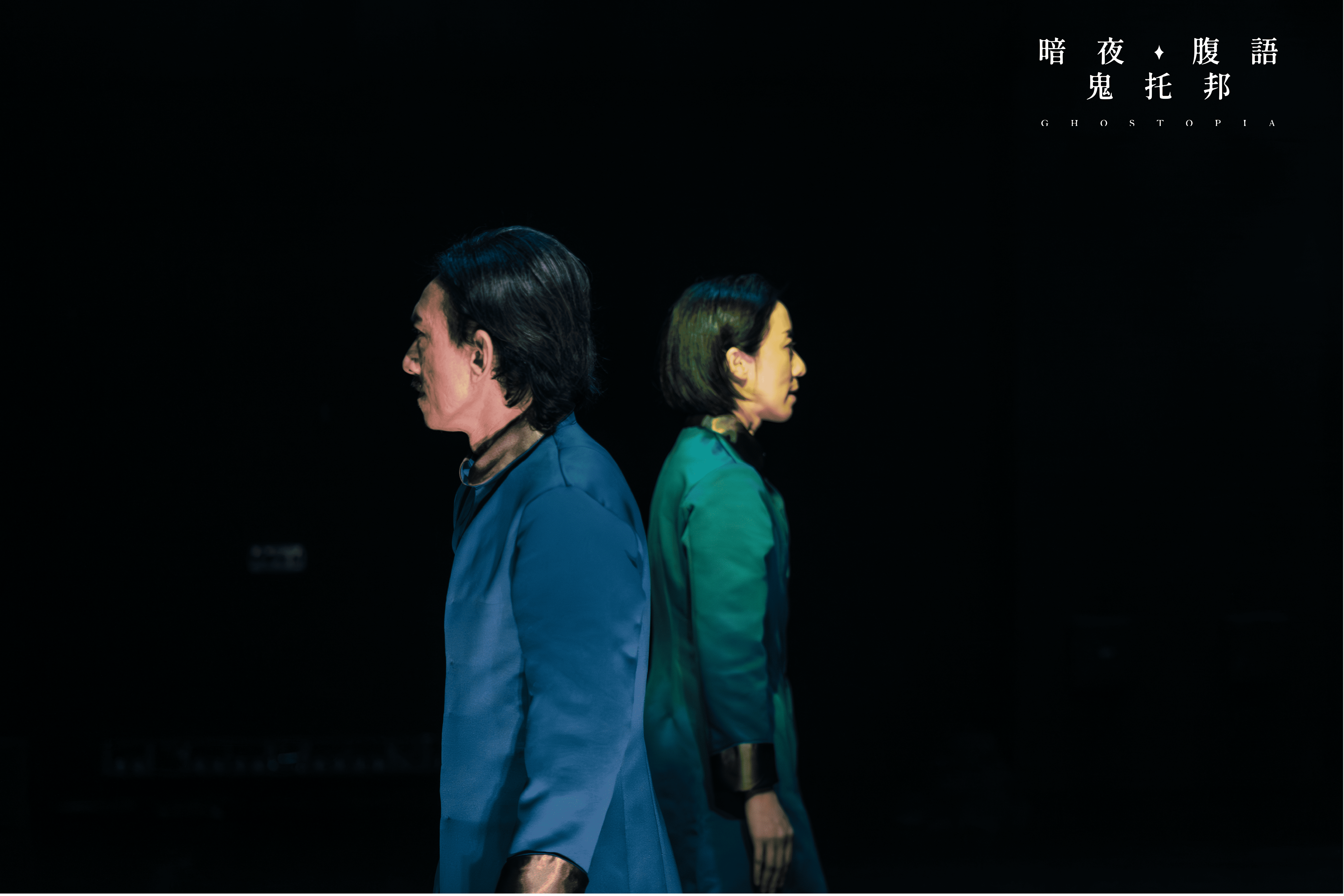

Setting aside sound and light effects, there is probably no better place than the theater to tell ghost stories. Adhering to the philosophy of “less is more,” approaching theatre uses a simple stage, consisting of a few platforms and a conspicuously long bamboo pole, on which the two actors, Cheng Yin-Chen and Koh, unleash their boundless imaginations. Such stories can only be told and reenacted in a theater setting. After all, ghost stories are not just about possession (acting), seances (on site), and deformation (theatrical transformation). They are also about yearning to “live.” Memories and emotions once attached to the body, from those on an individual level to those on national and historical levels, insist on not being forgotten.