2025 Autumn Dramaturgy and Theater Creation Courses: Moments Other than “When Angels Descend on the Stage”

By pupulin

TPAC Academy’s 2025 Autumn Dramaturgy and Theater Creation Courses delved into and provided fertile ground for the exploration of the themes of dramaturgy and theater creation. As four well-known scholars, artists, and dramaturgs imparted their knowledge through lectures and workshops, the significance of dramaturgy and theater creation was confirmed and reshaped, and new ideas were sparked. During a dramaturgy workshop, Wang Shi-Wei shared that no matter if talking about an actor, a director, or a playwright, no one can fully control a work. They can only move forward amid uncertainty, waiting for that moment “when angels descend.” In this course series, it is believed that all participants experienced or came closer than ever to experiencing that exhilarating moment “when all things naturally align.”

How has French drama evolved?

France stands out in the theater world. Lilly Yang has devoted her life to studying French theater. In her lectures, she first analyzed how French theater see-sawed among three paths during the 20th century, from the huge impact that political theater had on French society to the rise of people’s theater (theater for all people) which focused on “who can watch dramas and for whom dramas are performed,” and, finally, to the gradual development of the system of great directors after the 1970s.

Yang cited Paul Claudel’s work Le Soulier de satin as an important turning point, resulting in the ushering in of a new era for French theater in the 21st century. Le Soulier de satin has an extremely avant-garde cultural vision and theatrical presentation, with a script that is radical in scale and form. Breaking through the monotony of classic French drama, there is no depiction of a realistic world. Rather, its narrative is disjointed and chaotic, as well as filled with passion. This work had a profound impact on the new generation of directors.

People’s theater has been organically and fluidly redefined across generations. Yang gave an example of Théâtre du Soleil. Théâtre du Soleil does not pursue elitism. Rather, this theater company wants audiences to enjoy dramas as casually and naturally as they do picnics. At the same time, actors are expected to excel in all areas: physicality, voice, music, and collective creation. Deeply influenced by Eastern dramas, this theater company emphasizes physical expression and requires that emotions be amplified into discernible physical forms. Its most distinctive characteristic is the lack of repetition – no work uses the same performance language more than once.

By the 1990s, a generational break had occurred in European theater, with the ushering in of new directors. In 1980s German theater, Peter Stein was a leading figure. His highly successful performances led to the establishment of a powerful theatrical language, which even became part of the regular vocabulary of Western theater. In a short period of time, French theater lost two of its great directors, with the passing of Antoine Vitez in 1992 and Patrice Chéreau’s shift to filmmaking. As such, this generation of directors often refers to itself as the “fatherless generation.”

This new generation of directors has taken an exploratory approach to the creation of theatrical works, overturning established frameworks. This has resulted in the emergence of two paths. One is “stage performance-centered,” with narrative strategies that include deconstruction, intense music, multimedia technology, high levels of stylization, and emphasis on accessibility. Audiences clearly know they are watching a drama and that it must receive their full attention. The other is “script-centered,” which has been less common but does exist. The focus is on the writing structure of the script, while refraining from explanation, to let the structure speak for itself. After the 1990s, alternative performance emerged and French theater saw a large number of works that could not be clearly classified. They were neither dramas nor musicals but had some similarity to operas. They incorporated a little bit of everything.

The new generation of directors broke free from the critical approach of veteran directors. They did not seek direct explanations of the world, nor did they bear any so-called social or historical mission. They were unwilling to use drama as “a tool for analyzing reality.” Yang also talked about the creative characteristics of Stéphane Braunschweig, who among this new generation of directors she admires most. As a highly rational and intellectual director, Braunschweig rigorously analyzes scripts. Moreover, he has overseen the stage design for almost every one of his works, deliberately creating a gap between the stage design and the script, which forces the audience to pay renewed attention to the script.

For example, in his directorial masterpiece, The Seagull, the audience quickly realized that it was not the performance of The Seagull that they were expecting. Rather, it was more like a discussion of drama itself. The play-within-a-play at the end of the first act resulted in mirroring of the characters and the audience, while his meticulously crafted stage carried sharp themes about how drama is produced and viewed and the adjustment of the dominance of desire. Braunschweig is an important director who has inherited “the rigor of the previous generation’s scripts,” while implementing “the stage language of the new generation.”

【Lecture 1】Discovering French Theater and Drama by Lilly Yang. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

【Lecture 1】Discovering French Theater and Drama by Lilly Yang. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

Portrayals of loneliness and isolation

Changes taking place in the theater reflect the turmoil of the world. Lecturer Lo Shih-Lung used “shout” and “the end of the world” as the key word and phrase to focus on the similarities in the marginalization of Taiwan and Northern Europe, both of which yearn to be seen by the world. He explained that the so-called end of the world is a universal cultural feeling. Then, he introduced Norway, a geographically remote and sparsely populated country that produced Henrik Ibsen and Jon Fosse, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2023. This was followed by a discussion of Norway’s geography, population, and language, especially the coexistence of two forms of written Norwegian, and the history of its language and nation building following a long period of Danish rule. He explained how Norway’s peripheral location and internal tension have shaped a unique and intense cultural and theatrical voice, as he laid the foundation and provided the background for understanding contemporary Nordic drama.

How did language become a core issue in literature, politics and identity? Lo revealed that after Norway gained independence, there was a reconsideration of whether its own experiences should be recorded in its own language, due to the profound Danish influence on written Norwegian. Linguists studied folk song lyrics and local vocabularies to construct a writing system, which was named New Norwegian (Nynorsk). Although called “new,” it is based on even older linguistic roots. The language policy of that time required that the entire population learn both writing systems simultaneously, which sparked intense controversy and political opposition. This tension was brought to the forefront when Fosse won the Noble Prize in Literature for his works written in Nynorsk. This forced that country to respond head on to the relationships among language, literature, and cultural values and then to use public resources to support relevant research, translation, and promotion.

In this context, Lo placed Fosse into the history of Norwegian theater, which he traced back to Ibsen. Although these two have very different styles, they both possess a deep concern for language and local experiences. Ibsen gradually incorporated local language sensibilities into the Norwegian language framework, sculpting a believable language of the Norwegian middle class. The symbolic, death, and isolation elements in his later works are important clues to the continuation and transformation of Fosse’s dramas today. This is the key reason that these two have often been juxtaposed and compared.

Fosse was born in 1959 along Norway’s western coast and now lives in Bergen. In his early years, he wrote works in Nynorsk and in his 30s he was the recipient of the Nynorsk Literature Prize. In 2023, at the age of 64, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. There is an anecdote that upon learning of his Nobel Prize he calmly went for a drive to see the fjords, reflecting the isolation, loneliness, and loner aspects of his personality and works.

As Lo recounted Fosse’s life experiences, he pointed out that Fosse has a high level of sensitivity to music. As a young man, Fosse left home to play in a band. Later in his life, he began listening exclusively to the music of Bach. His musical background is considered the source of the intense rhythms, phrasing, pauses, and repetitive structure of his works. His scripts read like poems and have a musical quality to them. He offered examples of poems about the relationships between humans and nature, interpersonal relationships, and life and death, which featured highly restrained emotions and revealed his keen sensitivity to beauty.

Fosse deliberately reduces the information density of language. His works are not like traditional dramas in which the narrative is advanced through plot and conflict. Rather, he creates emotional space within pauses, silence, and poetic rhythm. As such, loneliness is a state that is “felt” rather than explained. Over the past 30 years, his scripts have inspired various director versions and have even been adapted for circus performances and operas, revealing their highly open form.

Minimalism is the core characteristic of Fosse’s plays. He leaves room for interpretation, stripping away character identities, backgrounds, ages, occupations, dramatic conflicts, and biographical details to leave only the most fundamental relationship structures. He also boldly pushes the boundaries of reality, using non-everyday settings such as the seaside, a sinking ship, and a cemetery to illuminate the essence of humanity. This is a crucial difference from other contemporary playwrights who tend to focus on everyday urban life, depicting loneliness within the confines of real social settings.

.jpg) 【Lecture 2】Our Time, Our Jon Fosse by Shih-Lung Lo. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

【Lecture 2】Our Time, Our Jon Fosse by Shih-Lung Lo. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

An artist’s confession of self and non-self

Lin Hwai-Min’s discussions of his training methods and approach to artistic creation were like his performances, captivating. In his lectures, Lin recounted a pivotal period in his life – between the pausing and restarting of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre. In 1988, at the start of Cloud Gate’s hiatus, he did not immediately throw himself into creating. Instead, he chose to leave his familiar way of working and embark on a long period of travel and study. He visited Xian, Luoyang, and Dunhuang in China to experience traditional Chinese culture firsthand, which vastly differed from his imagination of it. He also visited the US and Indonesia and ended up staying in Bali for a long time, immersing himself in Hindu culture and the world of epic poems and myths. During that time, he rarely consciously watched performances. Rather, he spent his time visiting museums, reading books, and focusing on life, allowing what he experienced to slowly seep into his being. The three years of Cloud Gate’s hiatus, which on the surface appeared to be a blank slate, were a crucial time for him to readjust his creative vision and life rhythms.

The 1991 reboot of Cloud Gate was not driven by ambition. Rather, it was a decision to “go back and see if we could do it again.” Lin admitted that his greatest assurance at that time was the belief that, “We could always shut it down again.” This meant that he was not bound by success or failure. Before and after the reboot, the members of Cloud Gate pursued further studies and accumulated professional expertise. At the same time, business and academic figures, such as Lee Yuan-Tseh, were invited to join the board of directors. They not only brought resources, but also a calm and pragmatic way of thinking, enabling Cloud Gate to stand more firmly under pressure and in the face of reality. This support quickly translated into action following a fire at Cloud Gate’s rehearsal space in 2008, leading to the birth of today’s Cloud Gate Theater in Tamsui.

Lin began a lecture on his creative process by talking about “music.” He recalled Cloud Gate’s early close collaborations with contemporary Taiwanese composers, noting that Cloud Gate had been an important platform for launching many locally produced compositions to large audiences. However, with the increase in overseas tours, a faster creative pace, and the difficulties involved in music production and licensing, commissioned compositions gradually became harder to come by. This led him to visit the large music collection that he had amassed. Nine Songs marked a turning point, as it was not based on a single culture or the music of a single country or ethnic group. Rather, it incorporated musical vocabularies from Tibet, Japan, and Europe, forming a cross-cultural dance aesthetic that transcended time and space. For him, music has never merely been an “accompaniment.” Instead, it is a structural element on par with costumes, stage, and dancers, requiring recombination and narrative structure.

Lin repeatedly emphasized that he has never considered himself a pure “choreographer.” He learned dance later than most in this profession and did not have the support of a comprehensive academic system, which forced him to constantly think about “how to bring a subject to life.” He cannot read sheet music or accurately count beats. However, as he is extremely dependent on music, he relies on intuition and repeated listening. Amid his limitations, he has found methods that work for him.

He also spoke about his extreme reliance on life experience to create works. Seeing camellias in full bloom during his travels brought to mind lines from poems, words, and images. Seemingly unrelated words and scenes have been quietly tucked into his “pocket,” waiting to become material for a dance production one day. Music is often not “found” first. Rather, a melody is suddenly discovered lurking within the choreography that has taken shape. Slow music was chosen for Moon Water, while for other works rhythms were extracted from the original dance music and reused, enabling dance to move between the familiar and the unfamiliar.

He described Songs of the Wanderers as a work completed with almost no music. His travels in India brought powerful pure feelings, as if washed in water, and the work flowed naturally from him. Later, a friend casually handed him a beat-up cassette tape. Without looking into its background, he continued choreographing with it solely on intuition. His search for the source of that music was fraught with difficulties. Eventually he found it in a Russian bookstore in New York. Many years later he discovered that he had bought that same CD long ago, but it had been sitting in a drawer. Even so, he deliberately avoids reading musicological or historical explanations, to prevent understanding from preceding feeling.

Finally, Lin returned to the fundamentals of physical training and aesthetics. He pointed out that dancers initially learn Western techniques but ultimately must return to their body’s own roots. Tai Chi, Qigong, Chinese martial arts, calligraphy, and architecture may seem different but share the same set of ethnic aesthetics and operation of qi. As dancers gradually enter these practices, an ancient yet familiar feeling is awakened in their bodies. This is not the result of learning new techniques. Rather, it is a restoration of internal order.

Some have described his works as “seeing dance, hearing time.” That is because the pace is often slow and there are pauses. For him, this is not a style. Rather, it is a necessary rhythm – a process of aligning breathing and enabling dancers to perceive one another. This so-called “skill” is not about technique. Rather, it is the result of time truly remaining in the body. When dancers quiet down and become more sensitive, their breathing becomes synchronized, and the music recedes into the background, such that the rhythms of the body form the core.

Looking back on Cloud Gate’s more than 40-year journey, Lin denied having any so-called “grand ambitions.” He said that choreography is merely a means. What he truly cares about is influencing and bringing solace to people from all levels of society – even if it is just enabling someone crammed into a small room after work to briefly enter a quiet and vast world through music. Along the way, there have been setbacks, difficulties, and uncertainties but it is precisely because he did not set lofty goals that he has been able to keep going step by step. In the end, he has come to believe: If you are on the right track, close the door, work hard, and time will leave behind that which is meant to be left behind.

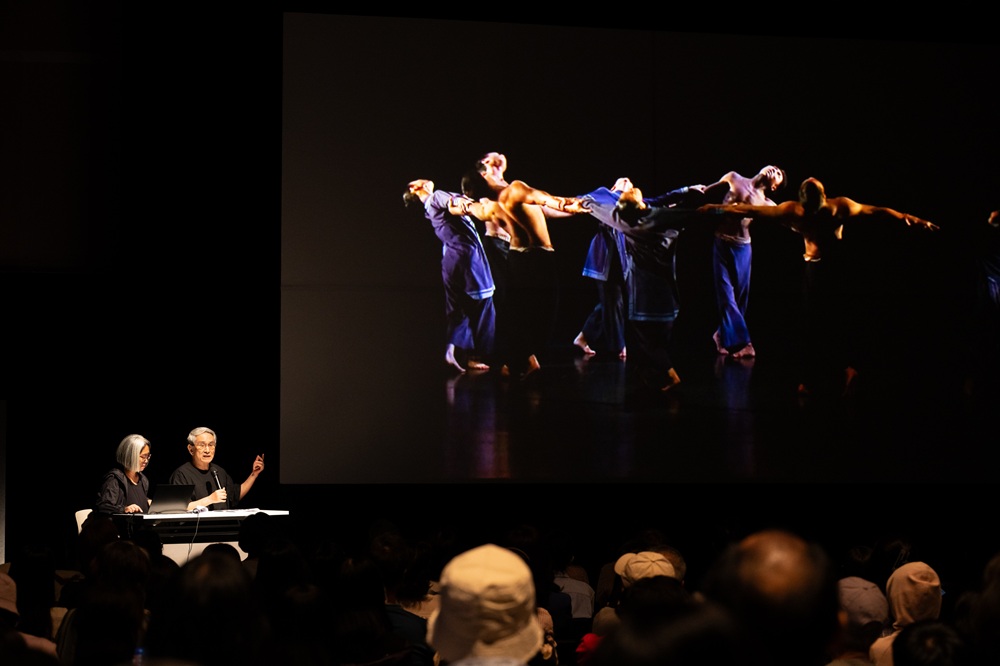

【Lecture 3】Lin Hwai-min’s Nomadic Journey with Cloud Gate by LIN Hwai-min. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

【Lecture 3】Lin Hwai-min’s Nomadic Journey with Cloud Gate by LIN Hwai-min. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

The eternal contemplation of spirit, thought, and action

Workshops led by Wang inspired creativity and broadened the views of participants on drama and the creative process. In one workshop, Wang focused on the relationships among silence, listening, and audience initiative and pointed out that silence is not a symbol of communication failure or absurdity. Rather, it is a form of ongoing exchange and even possibly rejection, respect, or complicity. Using Harold Pinter’s scripts as examples, silence does not mean that the characters are unable to understand one another. It is about what they are communicating and whether the audience is included in that communication. If handled improperly, silence becomes an awkward distance from which the audience must watch. This leads to the question of “whether listening is necessarily passive.” But perhaps the real question lies in how to make the audience realize that “receiving is a choice” or even how to transform listening into action, which often depends on how the relationship is established in the beginning.

Wang emphasized that watching is also a choice and choices inevitably come with responsibility. The reason why theater differs from others forms of entertainment, such as scrolling on a cell phone, is that the audience is aware that they are “responsible for watching.” With its origins in Greece, theater is an arena of action that is essentially political. This has resulted in the redefining of “entertainment.” He pointed out that entertainment is often based on familiar, predictable, and repetitive life experiences. However, the theater cannot and should not be regarded as an assembly line of productions that are meant to please everyone. The logic behind creation and the logic behind marketing/production are essentially incompatible. Excessive use of measurements such as KPIs and rates of return only obscures ways of thinking about creation.

He went further, noting that the reason that theaters are constantly forced to defend their “function,” is the excessive influence of mainstream social values. The value of theater lies precisely in its “uselessness” and a spirit that cannot be standardized. Entertainment and politics are not opposites. The moments that truly touch people are when theater transcends mere entertainment to reach the level of conflict and perception. Returning to creative practices, Wang also reminded participants that the focus should be on spirit and ways of thinking rather than on copying certain forms. Imitation is a necessary phase, but only through practice can one develop one’s style.

During a sharing session following a physical exercise, participant feedback revolved around “how feelings are activated” and “how states emerge.” Some did not understand the point of the exercise at first. They did not have a reaction until they “felt” the presence and proximity of others. Others realized that they hardly had a thought during the exercise. All they could do was follow the sequence of movements. It was only afterwards that they understood that it was a process of gradually pushing inward from “why?” Compared to the previous execution, this round was considered more nuanced because the participants no longer focused on their own movements. They also dealt with their reactions, states, and changes in their surroundings. They started to make choices between active response and passive acceptance, while continuing to feel.

There was also a discussion on ineffable key moments in a performance. One participant described such “a moment:” When everything naturally aligns, without assumptions, but perfectly reasonable timing, actions simply happen. Once you become aware of that state, it immediately disappears. It cannot be replicated and you only notice it in retrospect. This type of experience was also described as extremely instinctive and physical, as well as difficult to express in words. You are aware that you are performing, yet you become the character and feel as if you are on stage while, at the same time, watching yourself off stage.

Some participants pointed out that such a state is extremely rare, perhaps occurring only a few times in one’s life and is more a blessing than an achievement that has been deliberately pursued. What can be done is to reserve space and lingering effects for such moments, let go of the control over yourself, be prepared to accept uncertainty, and allow others and the environment in, so that there is an opportunity for “intangible power” to emerge.

.jpg) 【Workshop】In-Between Dramaturgy Workshop based on Jon Fosse's Plays by WANG Shi-Wei. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

【Workshop】In-Between Dramaturgy Workshop based on Jon Fosse's Plays by WANG Shi-Wei. (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

In a workshop that featured Tien Hsiao-Tzu, the focus of a physical exercise was not on completing a certain form or expressing a certain emotion. Rather, it was on revealing the inner state through clear and honest “choices” in terms of physical actions. The exercise began with walking. Waking is a neutral tangible point from which all movements originate, depart, and return. When a person chooses to initiate an action, other people respond with respective poses. These poses are not considered fixed, but rather a space, a process. The main points are how to enter, linger, and leave.

The choices available during this exercise included initiation, extension, imitation, superimposition, and interruption. Interruption is not failure, but a conscious ending, a return to walking, enabling the whole to flow again. Tien suggested not relying on emotions or feelings to drive actions but rather on movement between points in a space, because choices themselves naturally reveal how a person feels and exists. There is a constant shift in the process of internal and external interactions, which sometimes starts from the body, sometimes from a feeling. What is important is to realize that every choice is connected to personal experiences, background, and relationships, with adjustments and changes made through repeated attempts. At the same time, the present should be embraced without a rush to define the outcome.

.jpg) In-Between the Body and the Existence (feat. TIEN Hsiao-Tzu). (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)

In-Between the Body and the Existence (feat. TIEN Hsiao-Tzu). (Photo by Chen-Chou Chang)